On the left side of the display case, a dedicated section explores the art of drinking and serving within the convivial setting of Herculaneum, showcasing a selection of objects that combine function, formal elegance, and symbolic value.

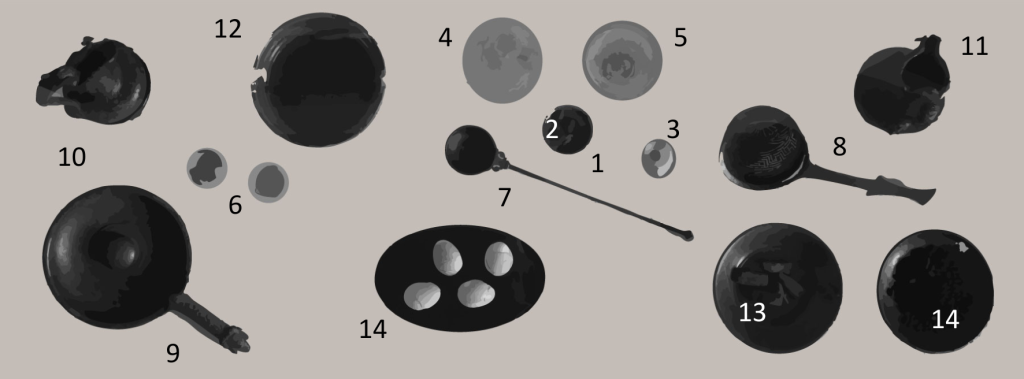

The first glass (1), made of thin transparent glass with greenish reflections, is decorated on the outside with spiral motifs, bucrania, and garlands framed in oval medallions—a repertoire of clear classical origin, rich in ritual and celebratory references.

The second glass (2), distinguished by slight indentations along its walls, reflects the influence of refined silver models with concave sides—a widely standardized type spread throughout the Empire, documented both in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Alongside the glasses, four bronze jugs illustrate the variety of forms and the sophistication of Roman tableware.

The first jug (3), with a bulbous body and “ear-shaped” handle, is finely decorated with vegetal motifs, chased reliefs, and a stylized acanthus leaf—hallmarks of high-quality Vesuvian production.

The second jug (4), with a pear-shaped profile and continuous line, features a vertical handle adorned with two stylized ibis heads, a thumb rest in the shape of an uraeus (sacred serpent), and a youthful satyr’s mask sculpted with delicate and lively features.

The third jug (5), with a trilobed mouth, bears a ribbon-like handle decorated with a vine tendril that ends in a youthful figure with open arms and a silenus mask, rendered with a deeply expressive face, furrowed brow, and curled beard.

The fourth jug (6), also trilobed, is enriched with a stylized lion’s head protome and a child’s head. Both elements, applied to the handle, hold decorative and symbolic significance. The trilobed shape, also common in glass and ceramic vessels, was widely used for its elegant functionality.

Of particular note is a skyphos (7 – a drinking cup) in glazed ceramic, with a green exterior and yellow interior. The bowl is decorated with grape clusters and vine leaves arranged in two registers, separated by a grapevine. Attributed to a production center in Asia Minor—possibly Tarsus—this piece attests to the vast reach of commercial and cultural exchanges at the time.

A unique piece is a basket-shaped vessel (8) in bronze, inspired by the woven baskets used by fishermen. Dating from the 1st to 2nd century AD, it features a ribbon handle connected by curved arms and decorated with a double swan protome, rendered in elegant, stylized form. Likely used to serve fish or shellfish during banquets, it blends practical use with symbolic refinement.

Adding depth to the convivial narrative are carbonized organic remains, including pomegranate peels and seeds (9 – Punica granatum) and dates (10 – Phoenix dactylifera), prized foods that reflect refined tastes and trade links with the eastern Mediterranean, both presented in ceramic plates.

The section concludes with two small bronze statuettes. The first depicts a camel (11) laden with baskets containing carbonized dates, with the pulp still intact. The second represents a bull (12), an animal linked to the sacred and agricultural spheres of the banquet. Due to their shape and size, both figures may be interpreted as votive offerings or decorative elements tied to ritual practices in the domestic sphere.